Poster Pastor

A former ad man has built a personal museum for his prized possessions.

David Levy has an affinity for travel, sledding, wine, and among many other things, posters.

He seems not to merely dabble. His interest in sledding led him to patent a high-tech sled for adults, upon which he plies the slopes of the Austrian Alps. But that is another story altogether.

Inspiration struck when his wife felt she had enough of the hundreds of poster tubes cluttering the basement. Excited at the prospect of actually viewing his treasures, he began looking for a venue. Potential locations included a former church, hence the name The Church of the Holy Poster. The venue fell by the wayside, but the name stuck.

Levy calls the Church his Man-Cave. He offers his guests whatever beverage they desire. “It’s man-cave law.” Yet that might be the nearest thing to macho that happens at the Church. He explains the genesis of his interest in posters:

“I was in New York. There was an exhibition of Circus posters. I went to see them and I just got weak in the knees. As a baby copywriter on Madison Avenue the appeal of a poster advertising the circus, what they had done visually, the words, the power, the artistry, the entertainment value… I was seduced by it.”

“I had to buy a circus poster. But I couldn’t afford a circus poster. I was fortunate enough to discover a gentleman who had a collection of posters and I found one I could almost afford: three hundred dollars. Which, at the time was astronomically expensive. My rent wasn’t $300. I bought this poster. I didn’t eat much for a couple of months until I could afford another couple hundred dollars so I could frame the poster, so I could see it. That’s how it started.”

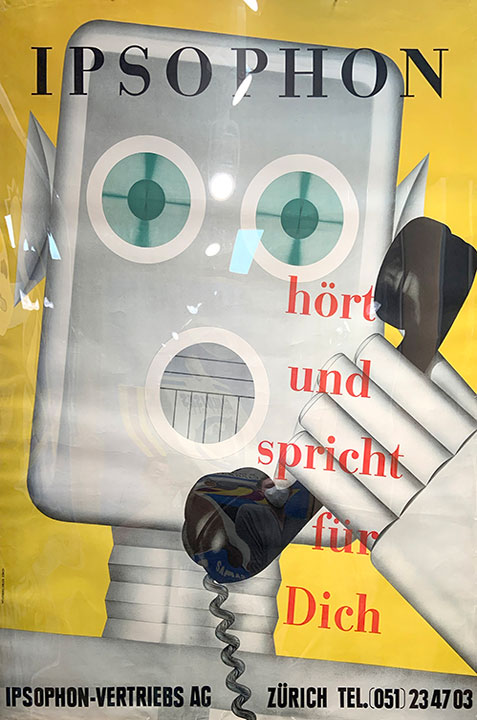

Posters in the Church date as far back as the 1800s and some are large. One is seven feet wide, another nine feet tall. It’s staggering to think that many were etched in reverse on stones because there was no other substrate available as stable. Each would weigh hundreds of pounds and would be hand-inked for each color printed. The distance between art and advertising was a rather short trip.

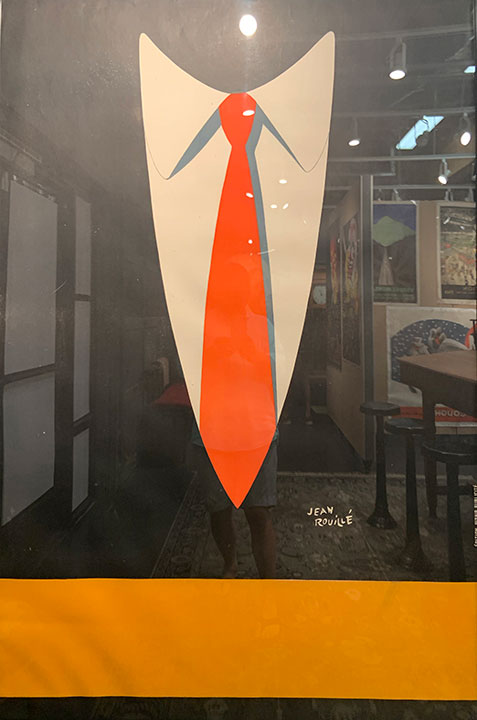

Levy is deftly aware that some of them are strange, even unattractive. But these things, these artifacts, occupy a special place for him. Not that they are holy, but that they provide a peek backwards at a moment in time. For the posters that have a backstory, Levy delivers.

Pointing out a poster encouraging the adoption of electricity, “At the time, homes were lit with gas. And you had to convince people of the the advantages – and safety – of electricity. They’re going to try and sell you on the alternating current… and the best part is you get a naked woman who has lights coming out of her head! Twenty years later, 1911: they’re still having exhibitions to sell you on electricity for your small business or on your farm… you get a naked lady, remember, and now she’s in chains. By 1920, she’s finally robed and is winged. 100 years ago, we had to work so hard to get people to adopt electricity? It baffles.”

The posters are wonderful. The collection of Seinfeld TV Guides from the 90s in the restroom a delight. The story – and results – of the space renovation are fascinating. But at the Church of the Holy Poster, the real gem is the man.

In a world starved for substance this hidden museum for one offers a fete. There is a bit of history, great banter, a glass of something refreshing and the bright company of a gentleman who entertains and elevates an afternoon well-spent.